Published 15 November 2021

Basseterre

Buckie Got It, St. Kitts and Nevis News Source

In the 1940s, around 400 men and women from the Caribbean boarded the George Washington ship for the United States. They landed in New York and took a train into Montreal, Canada, where they voluntarily enlisted to fight in World War II.

Canada was under British rule at the time and some loyal subjects of the British Empire who felt obligated to defend it against the Nazis, headed there to receive military training.

There, they joined other black people, some of who were descendants of black Americans who had escaped slavery through the Underground Railroad.

On Thursday, as the Commonwealth observed Remembrance Day, a memorial day to honour members of the armed forces who died in the line of duty during the World Wars, the History Channel debuted a new documentary that explored the untold stories of Black Canadian and Caribbean soldiers.

Titled Black Liberators WWII, the documentary was written and directed by Adrian Callender, and produced by Elizabeth Trojian and Elliott Halpern of Yap Films in collaboration with Kathy Grant of The Legacy Voices Project and Black Canadian Veterans Stories of War.

Black Liberators WWII sheds light on the important but almost forgotten efforts of Black soldiers who fought and died to rid the world of Nazism. For us in the Caribbean and the diaspora, it brought to light the role nationals of the region played in the Canadian armed forces.

The documentary tells the stories of the veterans through interviews with many of them who have since passed. Among them Owen Rowe, Grant’s father.

Rowe was from Barbados. He left at the age of 19 and served in the Canadian Royal Air Force.

He made his daughter promise to continue telling the stories of the experiences he and other Caribbean nationals faced while protecting the British Empire.

“He would share these stories and he had a reunion, the first reunion of West Indian soldiers in 1964, I was around three. He was always talking about West Indian soldiers and they even had a West Indian soldiers committee, they meet annually and had banquets and this went on for decades so I was able to go and gather their stories,” Grant recalled.

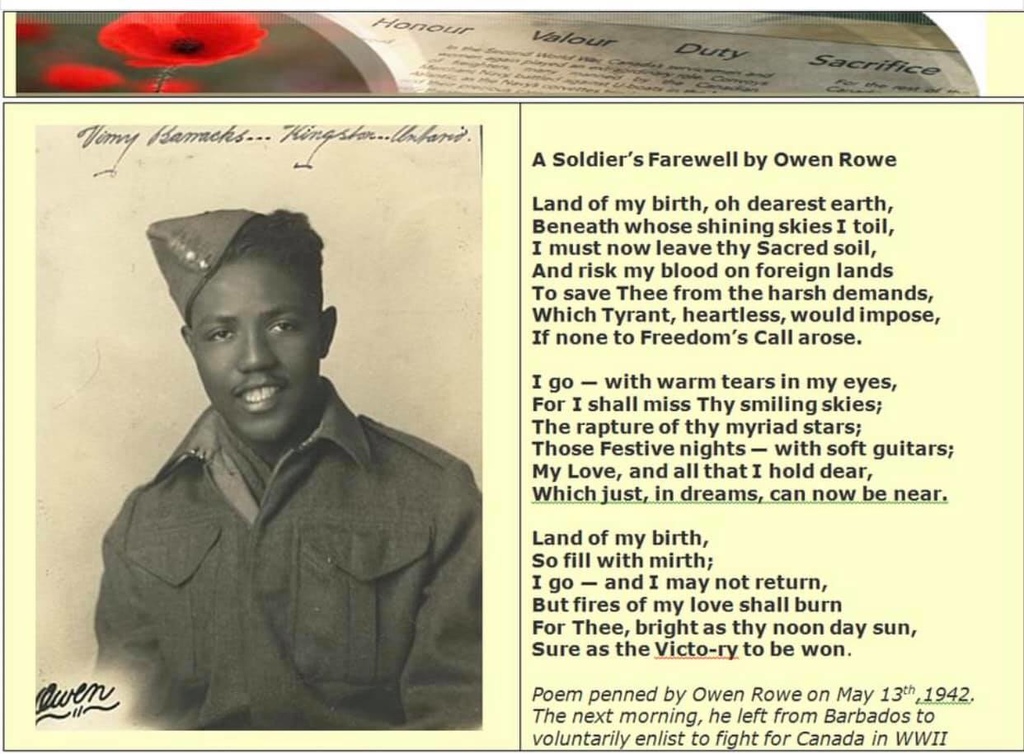

A poem written by Owen Rowe before he left Barbados to fight in the Canadian armed forces.

Grant was able to capture personal accounts, documents, and images from the veterans after noticing that the Veteran Affairs website had no information about them. She said the documentary has even flushed out some who are still alive.

Grant, who is a public historian and founder of Legacy Voices, which ensures Black Canadian history is documented and preserved, worked with YAP films as a lead historian for the documentary.

Callender said the interviews for the documentary were the first time so many of the veterans had told their stories and ventilated some of the trauma they experienced like Robert “Bud” Jones, who joined the army to support his parents in Chatham, Montreal.

Jones saw his friend Red die in battle while in the Netherlands and was pained to have to leave his body there.

“When we interviewed John Olbey, it was difficult for him to talk about these things. It is still difficult for him to talk about these things with his family. A lot of these gentlemen came back and held a lot of this stuff in, so you could imagine living as a young man from the age of 21 to your 90s with that always at the back of your mind,” said Callender.

Apart from peeling back the layers to understand how the soldiers’ experiences impacted their family life and interpersonal relations, the documentary also opens the door into an aspect of Canadian history that is only now being fully explored.

“We are in a really interesting moment in Canada, looking back at our history and asking different questions that weren’t asked before. Up until this moment, we haven’t been honest as a country of many of the darker tales and darker stories in Canada but we also haven’t been living up to the lofty words we like to share with other people in the world about how Canada values diversity. Now is a wonderful time because we are starting to look back and look at the hidden stories and this one is a fascinating one and will be a real revelation to Canadians when they see it,” Callender said.

Kathy Grant

For Caribbean people, the film is certainly a source of education and also provides a basis for us to understand the impact the wars had on our societies.

While some veterans stayed in their adopted homelands in pursuit of higher education or fighting racism to find employment, some returned to the Caribbean, more enlightened, more confident, more emboldened, and ready to take on the systems they left behind.

Dr Dalea Bean, a lecturer and historian at the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus, is featured in the film. She told Loop News that in the Jamaican context, returning soldiers definitely had an impact.

“Generally returning soldiers had a major impact on Jamaican society. Many went on to form or be active in trade unions (those that returned from World War I) and generally, soldiers came back to the Caribbean with new ideas about their place in a racialised society. Radical views lead to decolonisation from European powers and movements towards independence. Personally, many got higher education as lawyers, doctors, teachers, social workers, etc and therefore contributed to nation-building in important ways. This is true for both male and female soldiers,” she said via email.

Adrian Callender

Some returning soldiers from the Canadian and British armies went on to hold key positions of leadership in some islands.

Jamaica’s fourth Prime Minister Michael Manley served in the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1943, during World War II. At the end of the war, he attended the London School of Economics where he studied politics, philosophy, and economics.

Errol Barrow, Barbados’ first Prime Minister joined the Royal Air Force in November 1940 and served in World War II. He was a personal navigation officer to the Commander-in-Chief of the British Army at the Rhine between 1940 and 1942.

Robert Milton Cato, St Vincent and the Grenadines’ first prime Minister joined the First Canadian Army, attained the rank of Sergeant, and saw active service in France, Belgium, Holland, and Germany during World War II.

Sir Leo de Gale, first Governor-General of Grenada served in WWII from 1940 to 1945 as a gunner with the first Canada Survey Regiment (Royal Canadian Artillery) in Italy, France, Holland, Belgium, Germany, Britain and Canada, following which he returned to Grenada in 1945.

Grant’s father, who passed away in 2005 at the age of 82, served as an ambassador for Barbados.

For more information on black veterans visit the Black Canadian Website